Understanding DuckLake's Metadata Tables

A deep dive that reveals the secret of the LakeHouse architecture

Let’s take a look at the most important aspect of a LakeHouse Architecture…the metadata tables.

Reminder, go to my DuckLake deep dive here for a refresher on getting it up and running using the DuckLake CLI.

Lakehouse metadata tables are designed to capture data about different actions taken on parquet files in a storage bucket. It treats the storage bucket of parquets as a database. The big win with a Lakehouse is how you can run database commands on these files and it returns you data and aggregations. It’s really incredible considering what it would take for you to build something similar on your own.

The data in the metadata tables allow you to track changes over time. This provides an observability layer on a DuckLake. With DuckLake, there are a few options to choose from regarding where to store the metadata statistics. The first is DuckDB locally, which we will be using today. However this has some obvious limitations such as not allowing concurrent reads and writes. SQLite is also an option but has similar limitations to DuckDB. To build a productions level DuckLake you would either store the metadata tables in a Postgres database or you can also read here where I show you how to create one in MotherDuck. With that, let’s dive into the metadata tables.

First Attach a DuckLake

Remember, you first need to start up a DuckDB instance in your terminal and then attach a DuckLake to your instance. If this doesn’t make sense, go back to my original article about DuckLake for more info on this (see link above).

duckdbINSTALL DUCKLAKE;

LOAD DUCKLAKE;

ATTACH 'ducklake:my_ducklake.ducklake' AS my_ducklake;

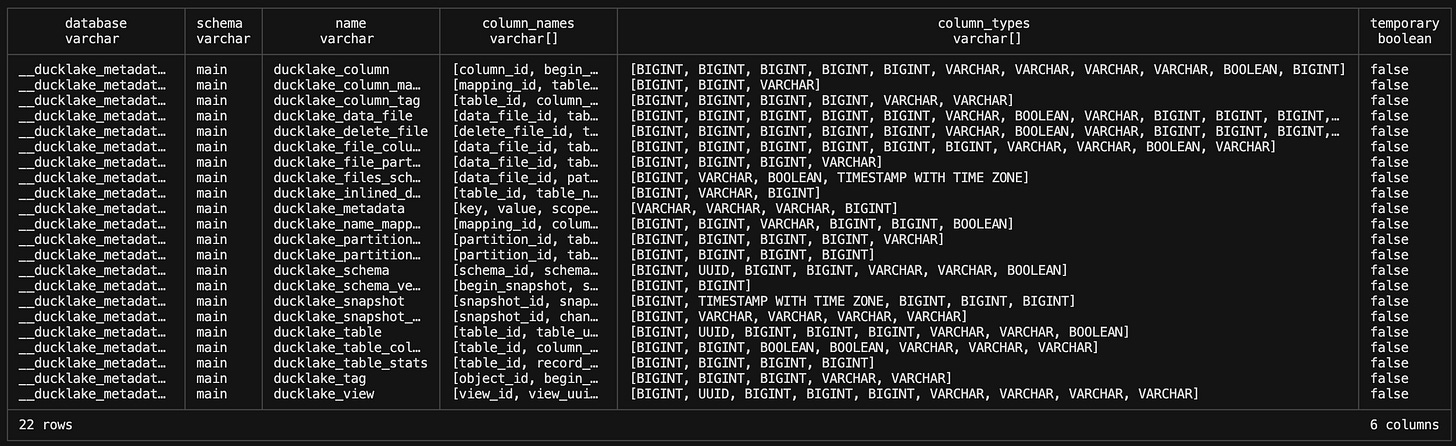

USE my_ducklake;There are 22 Metadata tables that are created when you create a DuckLake. You can quickly see all the metadata tables created by using the “show all tables” command in the terminal.

SHOW ALL TABLES;This table gives us a breakdown of what there is to query and how we need to query it. Namely, you use the “__ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake” prefix along with the table name to access these tables. Otherwise you’ll get an error. There are a lot of tables here, so for the sake of the length of this article we will focus on the top 11 the DuckLake’s overview page points out HERE.

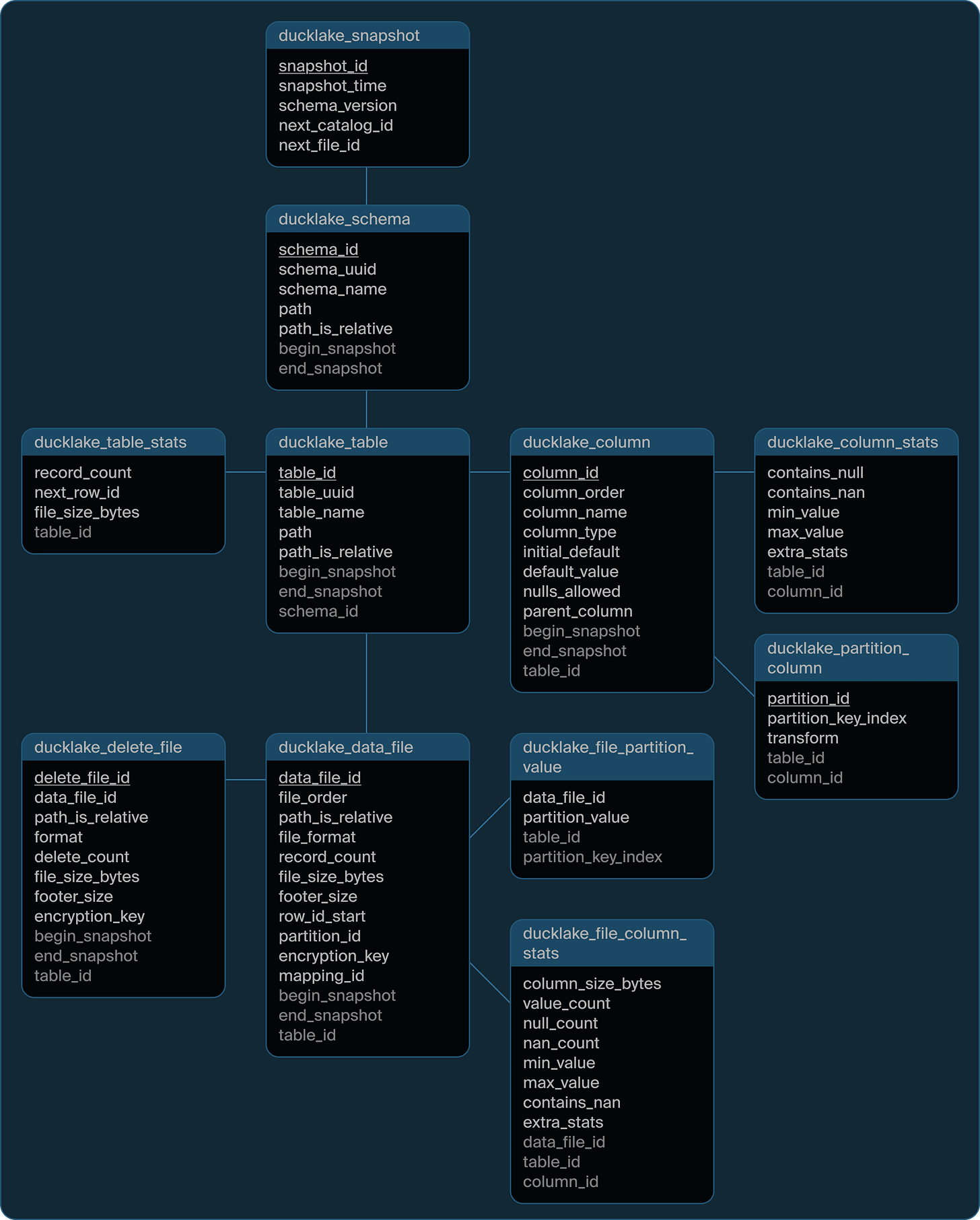

You can see a nice flow chart of the tables in the above link. You can query these tables before you add any data to them.

Snapshots

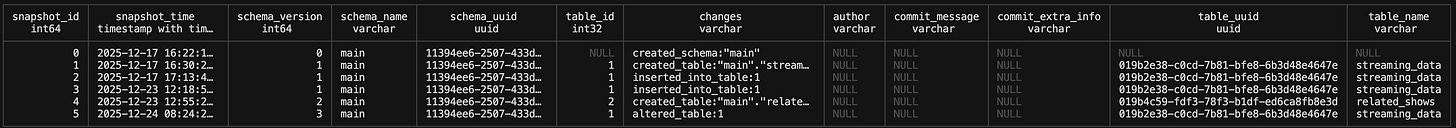

DuckLake has tables that shows you snapshot timestamps with id’s, schema versions and changes.

ducklake_snapshot

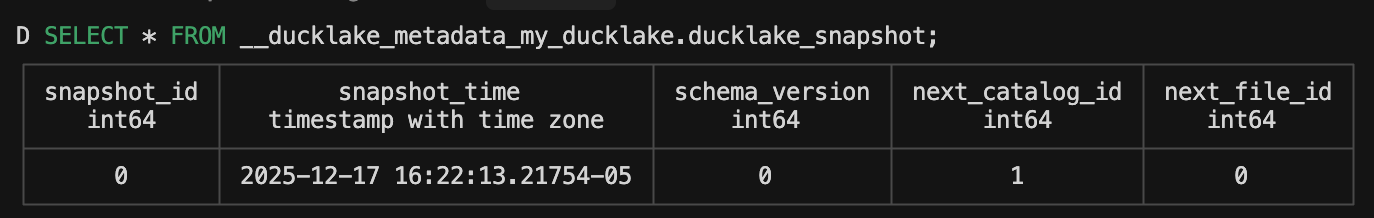

When you first create a DuckLake it creates a row of data in the snapshot table.

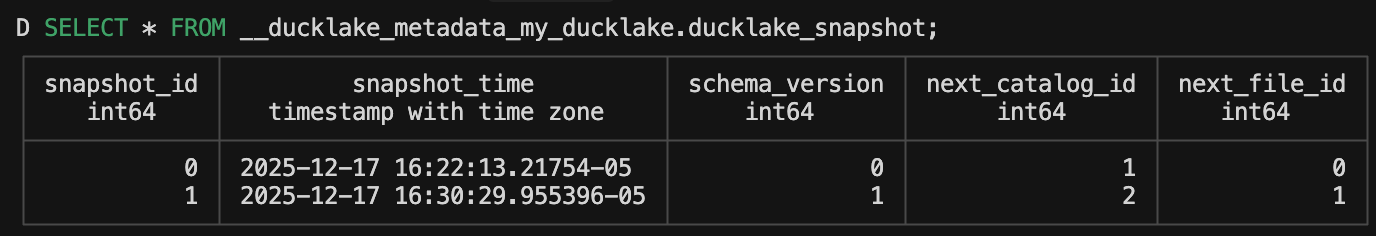

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot;When you create a table in the DuckLake, statistics about that table are updated in the snapshot metadata tables.

CREATE TABLE streaming_data

AS

FROM 'path_to_data';Now, DuckLake has a built in function that let’s you also view snapshot history and you’ll notice it is a little different.

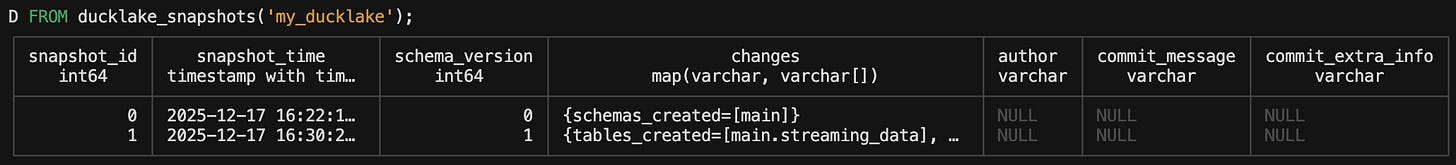

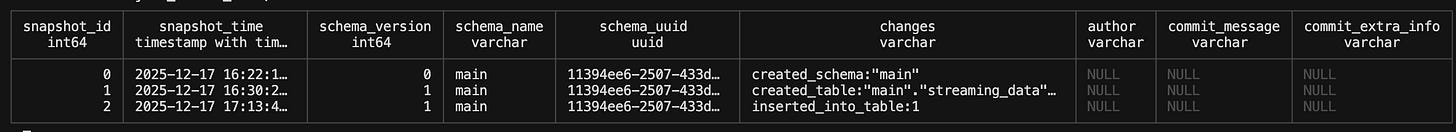

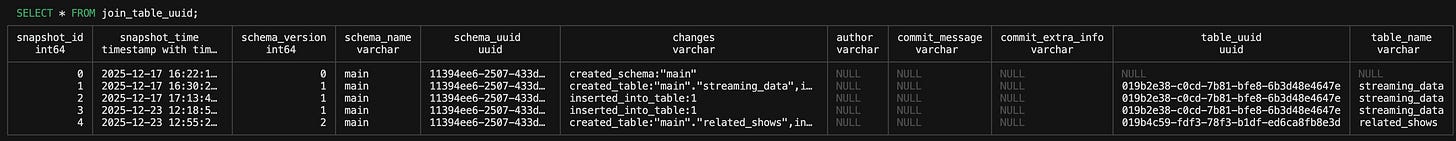

FROM ducklake_snapshots('my_ducklake');There’s a changes column as well as author, commit_message and commit_extra_info. These all live in another metadata table called ‘ducklake_snapshot_changes’.

ducklake_snapshot_changes

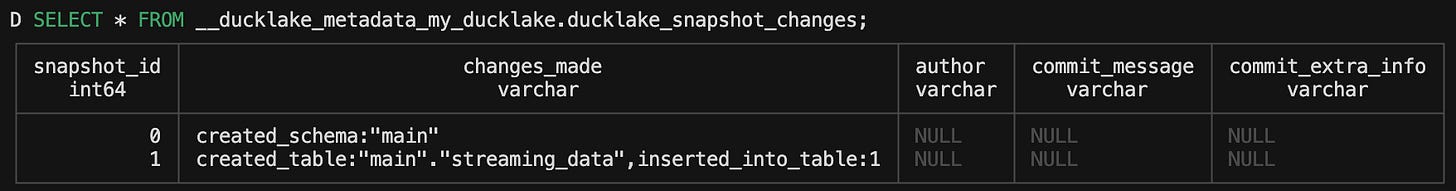

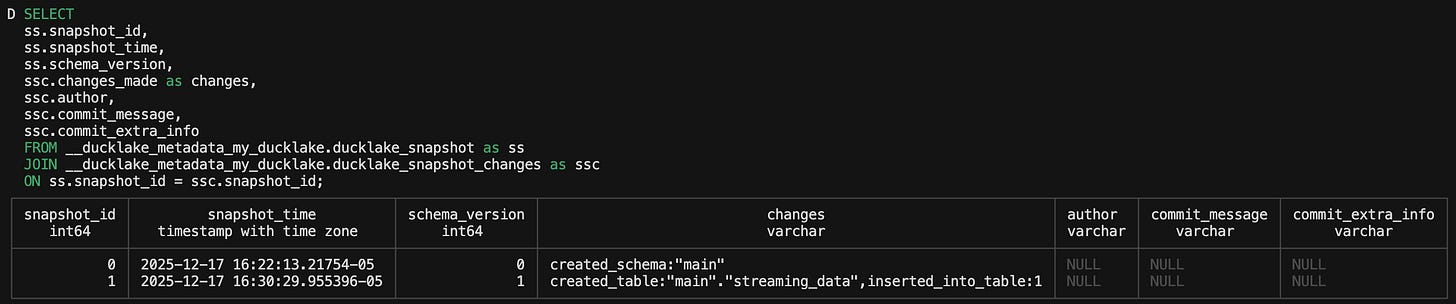

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot_changes;So we can recreate the ducklake_snapshots function with a query:

SELECT

ss.snapshot_id,

ss.snapshot_time,

ss.schema_version,

ssc.changes_made as changes,

ssc.author,

ssc.commit_message,

ssc.commit_extra_info

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot as ss

JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot_changes as ssc

ON ss.snapshot_id = ssc.snapshot_id;DuckLake Schema

Before we start looking at another set of tables, let’s append some more data to the current DuckLake so we have some more statistics to work with:

CALL ducklake_add_data_files(

'my_ducklake',

'streaming_data',

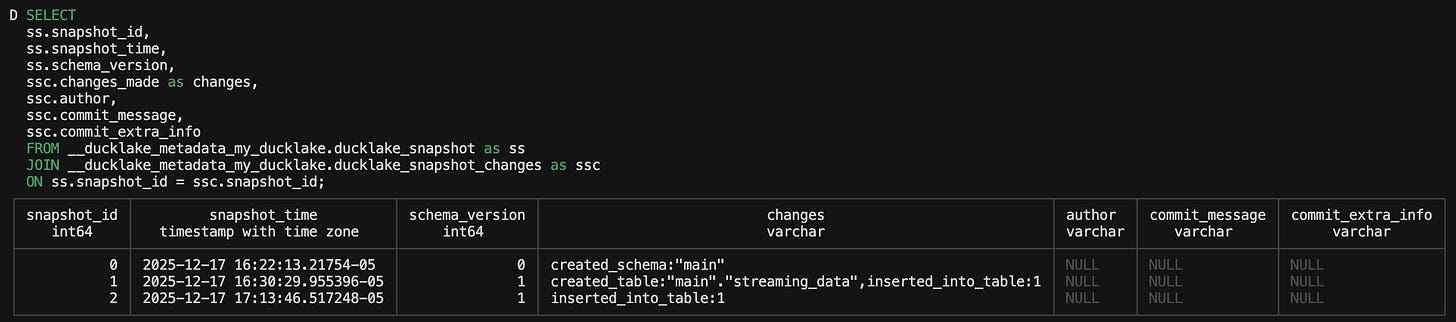

's3://path-to-file.parquet')The above query will append data to the current streaming_data table in the my_ducklake database. For a quick reference, the snapshot query we made now shows this:

ducklake_schema

We now have inserted_into_table showing in the changes column let’s look at the ducklake_schema table:

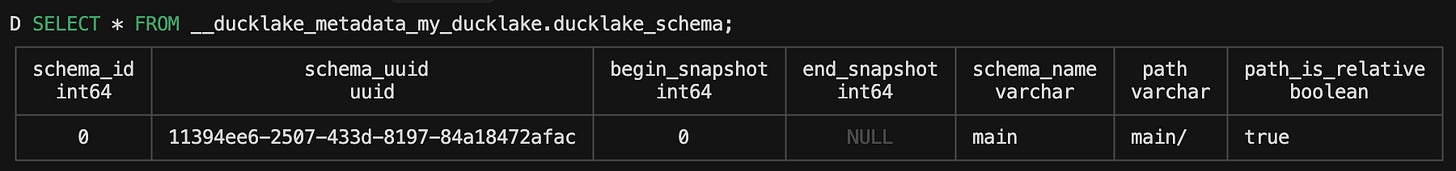

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_schema;You might get a little confused here. There are multiple schema_version id’s in the ducklake_snapshot table but only one row in the schema table itself. That’s because this is the table that has the id for the ACTUAL schema that was created (“main”). The main schema is created once and all subsequent updates to the table in the schema is captured in the snapshot table. However, the main schema is distinct and has just one id. Also, the begin_snapshot column can be joined to the schema_version column of the ducklake_snapshot table. In the snapshot table, the schema version of “0” is referencing the actual creation of the schema itself. The next versions in the schema table are “1” because a table has then been created in the schema. Once you add a table to a schema you get a new schema version in the snapshot table.

We can enrich our snapshot table some more by adding a schema_name column and then bringing in the schema UUID:

WITH snapshot_changes AS (

SELECT

ss.snapshot_id,

ss.snapshot_time,

ss.schema_version,

ssc.changes_made AS changes,

TRY_CAST(REGEXP_EXTRACT(ssc.changes_made, '_table:([0-9]+)', 1) AS INTEGER) AS table_id,

ssc.author,

ssc.commit_message,

ssc.commit_extra_info

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot as ss

JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot_changes as ssc

ON ss.snapshot_id = ssc.snapshot_id

),

join_schema_name AS (

SELECT

sc.*,

st.schema_name

FROM snapshot_changes sc

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_schema st

ON sc.snapshot_id = st.begin_snapshot

),

join_schema_uuid AS (

SELECT

jsn.snapshot_id,

jsn.snapshot_time,

jsn.schema_version,

COALESCE(jsn.schema_name, LAST_VALUE(jsn.schema_name IGNORE NULLS) OVER (ORDER BY jsn.snapshot_id)) AS schema_name,

COALESCE(dls.schema_uuid, LAST_VALUE(dls.schema_uuid IGNORE NULLS) OVER (ORDER BY jsn.snapshot_id)) AS schema_uuid,

jsn.table_id,

jsn.changes,

jsn.author,

jsn.commit_message,

jsn.commit_extra_info

FROM join_schema_name jsn

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_schema dls

ON jsn.schema_name = dls.schema_name

)

SELECT * FROM join_schema_uuid;We are going to once again add some more data to this table. This data will represent another day.

ducklake_table

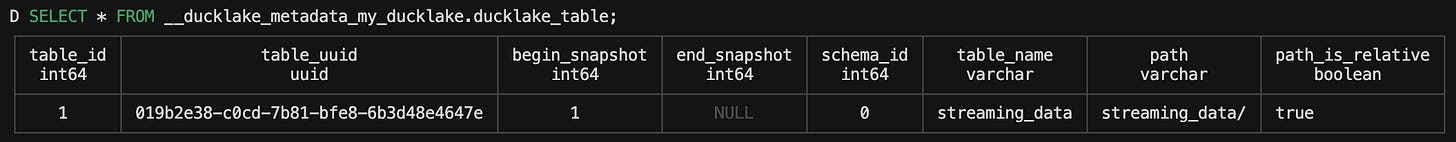

To get info about a table in the main branch you can look at ducklake_table. This table is similar to the schema table except now we have a UUID for the table itself along with a table name.

It also has a begin_snapshot column that can be joined to the snapshot_id of the ducklake_snapshot table. Additionally, you can join the table_id column to the schema_version column in the ducklake_snapshot table. Given that, we can append some similar SQL to our query above to enrich the query more with table information.

// Query above

join_table_uuid AS (

SELECT

jsu.*,

dt.table_uuid,

dt.table_name

FROM join_schema_uuid jsu

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table dt

ON jsu.table_id = dt.table_id

ORDER BY snapshot_id

)

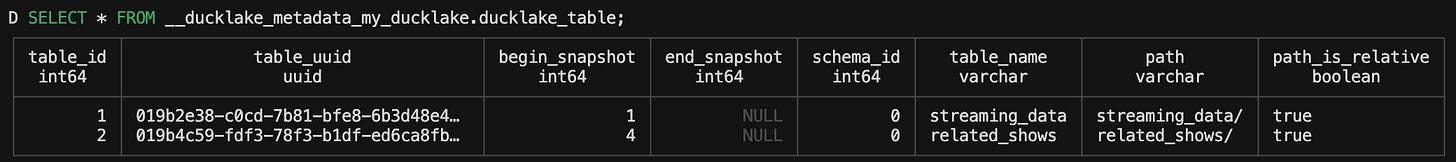

SELECT * FROM join_schema_uuid;So what happens if we add a new table to this schema? It’s certainly something we are allowed to do. A DuckLake can encompass multiple tables. Let’s bring in some different data for a new table and find out! I have another dataset I use that can be joined to the streaming_data synthetic dataset called related_shows:

CREATE TABLE related_shows

AS

FROM 'path_to_data';If we look at the ducklake_table table again we will see a new UUID for the new table, but also you will note that the begin_snapshot column is ‘4’. This allows us to join where these tables were created in the ducklake_snapshot table.

And if we run the updated query we have above then we will now see a new schema version and table name coming into it.

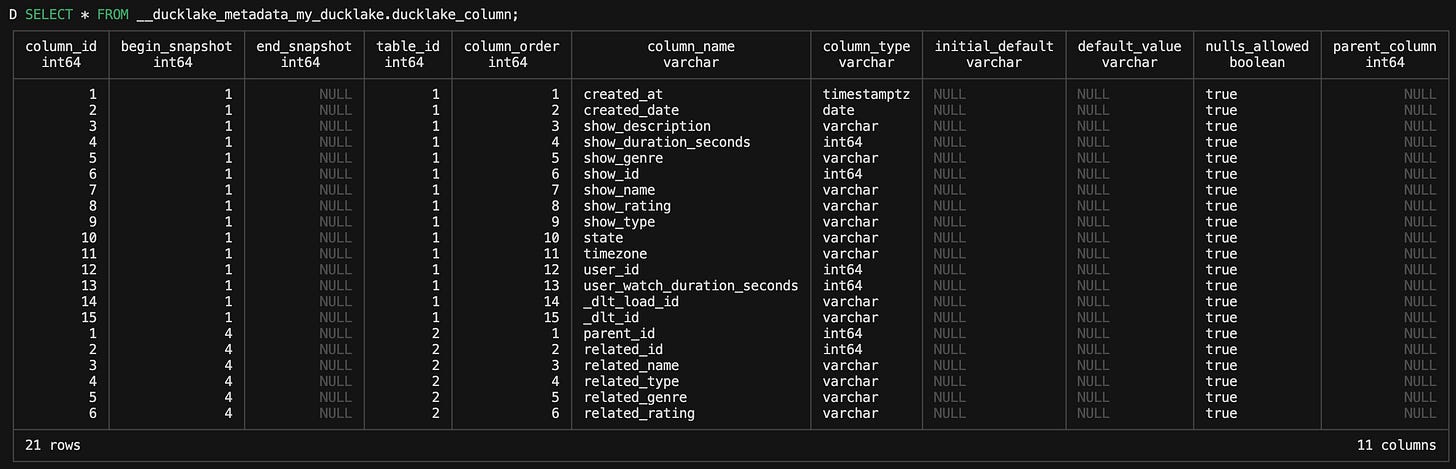

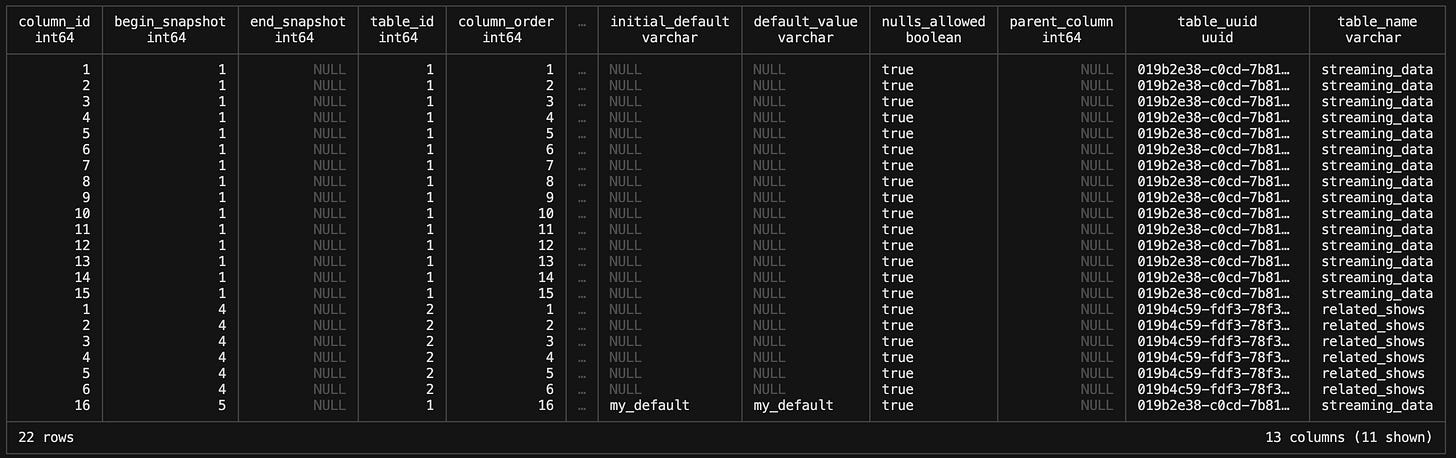

ducklake_column

DuckLake has a full schema explanation of all columns for all available tables as well as the ability to track schema evolution over time. The initial ducklake_column table for our tables looks like this:

You’ll notice that it has two different table_id values, which represent each of our tables we’ve created, as well as two different begin_snapshot values for each table. They are also ordered by table_id and then column id in ascending order.

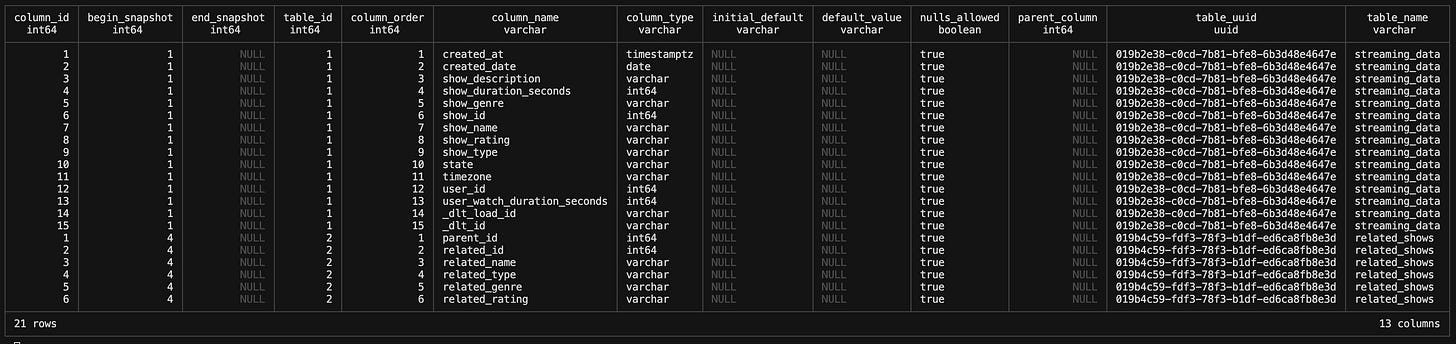

We can enrich this a bit more by bringing in the table names for the columns:

SELECT

dlc.*,

dlt.table_uuid,

dlt.table_name

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_column dlc

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table dlt

ON dlc.table_id = dlt.table_id;This will now give use some more verbose grouping columns to work with.

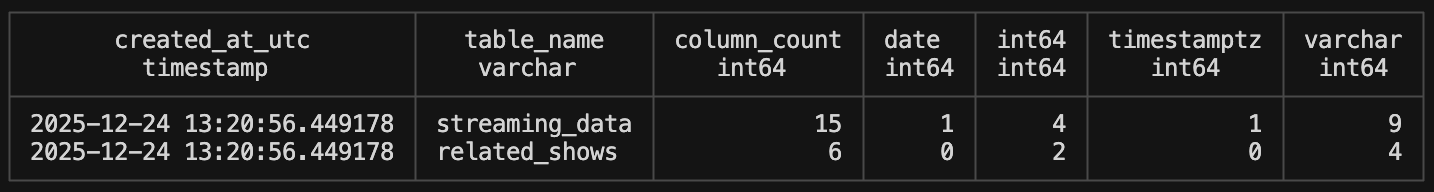

We could also bring in the schema here as well but that’s a bit overkill for what we are doing. However, now that we have table names in here we can create some basic statistics on the table schemas that read nicely:

WITH column_table AS (

SELECT

dlc.*,

dlt.table_uuid,

dlt.table_name

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_column dlc

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table dlt

ON dlc.table_id = dlt.table_id

),

column_count AS (

SELECT

table_name,

COUNT(column_order) as column_count

FROM column_table

GROUP BY table_name

),

column_type_count AS (

PIVOT column_table

ON column_type

USING COUNT(column_type)

GROUP BY table_name

)

SELECT

CURRENT_TIMESTAMP AT TIME ZONE 'UTC' AS created_at_utc,

cc.*,

ctc.*EXCLUDE(table_name)

FROM column_count cc

LEFT JOIN column_type_count ctc

ON cc.table_name = ctc.table_name;What is nice about DuckDB is that we can use the PIVOT command to spread out a column. This isn’t always available across other OLTP or OLAP databases. But we can see here that we get some nice high level statistics that we can look at over time. We can run this query and append it to the same table to see if things change over time. In fact, why don’t we add a new column to see how that looks.

ALTER TABLE streaming_data ADD COLUMN new_column VARCHAR DEFAULT 'my_default';See how the ducklake_table now has the new column referenced at the bottom of the table. That is because the new column has a new begin_snapshot value, which is what the table ultimately orders by.

This gives us visibility into schema evolution, which is an amazing feature of the DuckLake metadata tables. It allows us to see exactly what happened and when. This is most noted when we look at the joined query we have made above:

WITH snapshot_changes AS (

SELECT

ss.snapshot_id,

ss.snapshot_time,

ss.schema_version,

ssc.changes_made AS changes,

TRY_CAST(REGEXP_EXTRACT(ssc.changes_made, '_table:([0-9]+)', 1) AS INTEGER) AS table_id,

ssc.author,

ssc.commit_message,

ssc.commit_extra_info

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot as ss

JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot_changes as ssc

ON ss.snapshot_id = ssc.snapshot_id

),

join_schema_name AS (

SELECT

sc.*,

st.schema_name

FROM snapshot_changes sc

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_schema st

ON sc.snapshot_id = st.begin_snapshot

),

join_schema_uuid AS (

SELECT

jsn.snapshot_id,

jsn.snapshot_time,

jsn.schema_version,

COALESCE(jsn.schema_name, LAST_VALUE(jsn.schema_name IGNORE NULLS) OVER (ORDER BY jsn.snapshot_id)) AS schema_name,

COALESCE(dls.schema_uuid, LAST_VALUE(dls.schema_uuid IGNORE NULLS) OVER (ORDER BY jsn.snapshot_id)) AS schema_uuid,

jsn.table_id,

jsn.changes,

jsn.author,

jsn.commit_message,

jsn.commit_extra_info

FROM join_schema_name jsn

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_schema dls

ON jsn.schema_name = dls.schema_name

),

join_table_uuid AS (

SELECT

jsu.*,

dt.table_uuid,

dt.table_name

FROM join_schema_uuid jsu

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table dt

ON jsu.table_id = dt.table_id

ORDER BY snapshot_id

)

SELECT * FROM join_table_uuid;With this as the table output:

Statistics

We have now gotten to the portion of tables that gives us aggregated information about our DuckLake:

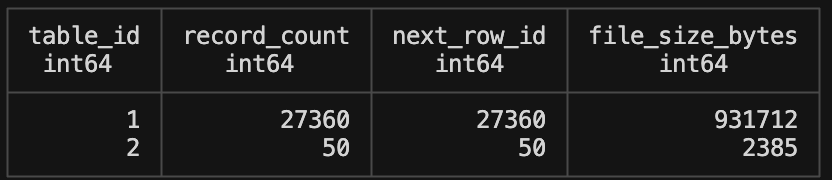

ducklake_table_stats

This is a very high level aggregate table that is probably best used to get record count very quickly in a join.

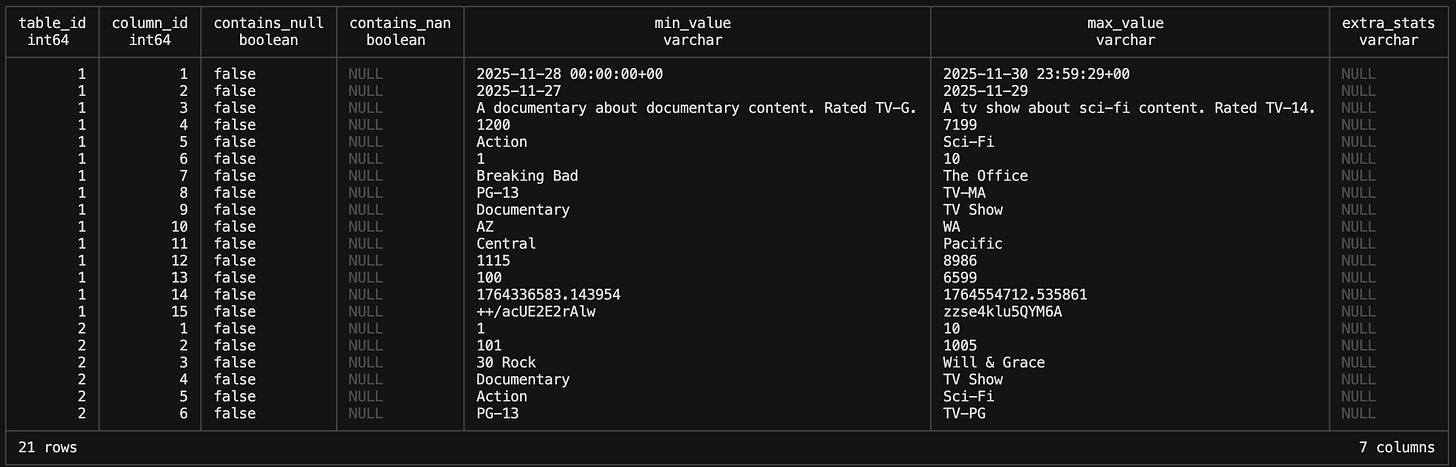

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table_stats;ducklake_table_column_stats

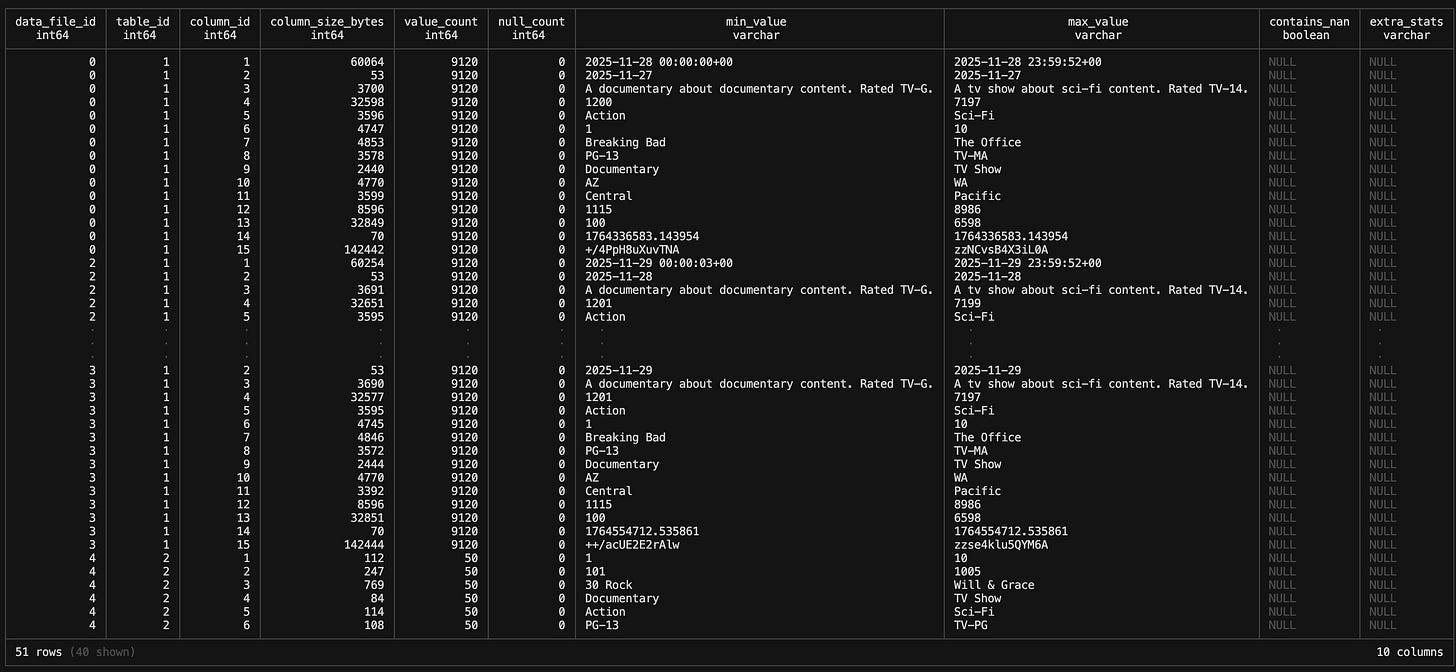

This is a very interesting table because it has min and max values for each column. Which is slightly more granular information than the ducklake_table table we were looking at above.

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_table_column_stats;If you look close, you will see that there are only 15 columns showing in this table. But why is that? We created a new column called “new_column” and we set a default value to it. Well, as of this writing we find what looks like a bug in DuckLake (a brand new project is gonna have em!). It took me a number of head scratching minutes to finally google the problem to learn an issue had been opened for the week prior (gah I had a chance at finally post a bug!). You can see the issue here.

ducklake_file_column_stats

You’ll see a similar bug in this table as the column we created with ALTER TABLE is not showing. Regardless of that open issue, you can see it is showing data for columns for each file that we added to the table. Very interesting to get that level of detail!

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_file_column_stats;Data Files and Tables

This tables keep track of the data files that were added or deleted in the DuckLake.

ducklake_data_file

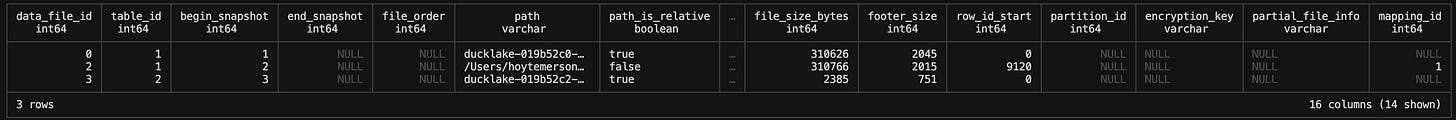

Each row in this table represents a data file and records where it lives, how big it is, how many rows it contains and how it fits into DuckLake’s versioned snapshot model. By using begin_snapshot and end_snapshot, DuckLake can determine exactly which files are active for any given snapshot, enabling ACID-style versioning and time travel. Additional metadata such as file order, partitions, row ID ranges, and optional encryption details allows to efficiently plan reads and understand how each file contributes to the logical table at query time.

SELECT * FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_data_file; The data_file_id column is the numeric identifier of the file. It is a primary key. data_file_id is incremented from next_file_id in the ducklake_snapshot table. So we can join those tables using begin_snapshot = snapshot_id. This will show us the size of the data file added at that snapshot and what row it started it.

SELECT

dls.*,

ddf.*

FROM __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_snapshot dls

LEFT JOIN __ducklake_metadata_my_ducklake.ducklake_data_file ddf

ON dls.snapshot_id = ddf.begin_snapshot

ORDER BY dls.snapshot_id;ducklake_delete_file

In DuckLake you may want to delete data files that are either a part of an expired snapshot or are simply not tracked by DuckLake anymore (i.e., orphaned files). There are a couple manual functions that are used to delete these. Those files will end up in this table. Given that is out of scope with what I’m doing with my DuckLake I will leave it at this. But just FYI, this table has the same primary key and join as the ducklake_data_file table above.

Partitioning Information

This is the last group of tables we will look at. You can partition a DuckLake and these tables will show you useful information about the partitions.

Partitioning can be done with one query:

ALTER TABLE streaming_data SET PARTITIONED BY (year(created_at), month(created_at));You then need to add another data file to the DuckLake because the partitioning starts on data added after you set the partition column. You will use an INSERT command to add this data.

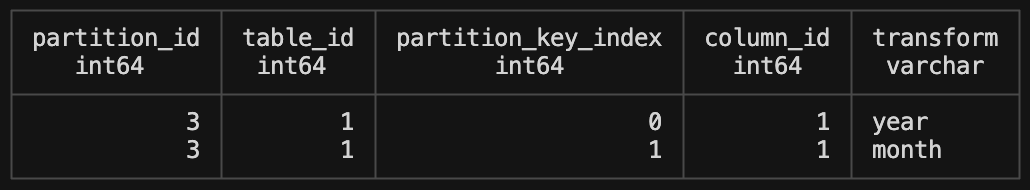

INSERT INTO streaming_data SELECT * FROM 'path/to/parquet';ducklake_partition_column

This table shows you the partition columns names, table id and column position id. It comes in handy when you want to see that info quickly and conveniently.

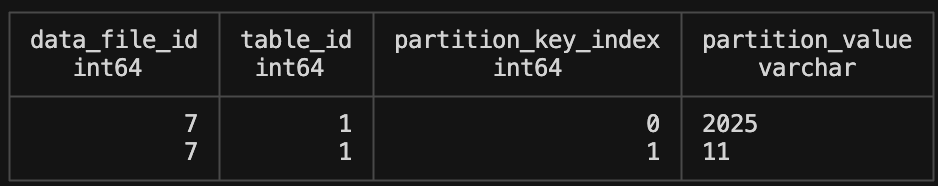

ducklake_file_partition_value

The file partition value table defines which data file belongs to which partition. You have data_file_id and table_id as primary and foreign keys for joining onto your snapshot, partition column or data file tables to add more detail to what data specifically sits in what partition. A nice to have when

Conclusion

Diving deep into DuckLake over the last few months has been a lot of fun. The Lakehouse architecture has finally clicked for me, even though DuckLake takes a different approach to metadata storage than Apache Iceberg does. Regardless, I’ve realized that this might be my preferred form of a database, vs a data warehouse, because I work in analytics. Most of the time, the data I want to access needs to go to a frontend analytics system like Streamlit. To optimize those reads, I tend to push data from a data warehouse like BigQuery to parquets in file storage. But I’m starting to wonder if that’s what needs to really happen, or if instead I simply push queries from source tables directly to parquets in storage and remove the DW layer. As long as I use something like DuckLake for metadata storage and tracking it creates an exciting alternative to keeping all your data in the proprietary table formats of BigQuery, Snowflake, Azure etc. And on top of that, these tables allow for a clear observability layer that let’s you keep track of TONS of information about the Lakehouse. This article concludes my deep dive series in DuckLake, but the journey is far from over. I expect to bring DuckLake into the mix for many future articles about new tech tools and subjects. I am now very bullish on Lakehouses and DuckLake in general.

That image is hilarious