The “Shift Left” movement. It has gained momentum in the last few months, but has been talked about and discussed online quite a bit in the last couple years specifically. At the heart of Shift Left is the idea of Data Contracts. Data Contracts, at an abstract level, are meant to offer a consistent explanation of data as it moves through its lifecycle from the source to the end result. It has also created a bit of controversy as to what it actually means and who should be in charge of it. I do my best below to offer a real world explanation and use case leveraging GCP to propose data contracts to your org.

What is a Data Contract?

At its core, a Data Contract is a static schema that persists from the source that emits an event onto wherever else the data travels. While static, the schema can still be versioned, but that must be done incrementally. However, the more holistic view of a Data Contract also involves additional details such as:

Data owner

Schema definitions

Documentation

Data categorization

Service-level agreements (SLAs)

Versioning and change management policies

The above list is a hill only the Shift Left Maximalists will die on. Given I’m not one of those, I focus on the most important element that a Data Contract offers, which is a governed, version controlled schema of every event that is emitted. From that first principle, you need to make a technical decision about what format you will leverage to facilitate these schemas and what the message platform will be. Since I am most familiar with the GCP stack, I like to use PubSub. It is free to use and costs should be essentially null if you want to test the waters around Data Contracts. Now that I know what my message platform will be, I have some criteria that has to be met so that the events will properly work in the platform. PubSub has the ability to accept both Protocol Buffer or Avro schemas. If you are unfamiliar with either of these, then best to get situated first before jumping into Data Contracts. For me personally, I prefer Protocol Buffers because the schema is more concise in my opinion and also they handle datatypes in a way I prefer compared to Avro.

So at this point we have made these technical decision:

The messages emitted will have a set, version controlled schema Data Contract

GCP PubSub will be the message platform we will send the events to

The event messages will leverage Protocol Buffer schemas

At this point, depending on what team you are on (Analytics, Data Engineering, Software Engineering) will determine how far left you need to shift to get these Data Contracts implemented.

Who Needs to be Involved?

The farthest upstream we need to go to implement a Data Contract is the Software Engineers in charge of the source code that creates the events. In my case, I wanted to implement Data Contracts on the events that were being emitted from an automation solution the robotics start up I worked at was building. So the source of the events themselves was a physical machine built by Mechanical Engineers. However, Software Engineers were the owners of the source code that would actually create these events. At the time, there were events being emitted, but they lacked any schema governance. They were being pushed through an internally built message pipeline that had no fault tolerance, message queue and robust schema validation. Least to say, it was massively prone to failure. And when those failures occurred, it gave our Analytics a 1-2 week setback. Getting surprised like that was also due to the fact that there was zero data pipeline health visibility and no quality checks on many of the tables. Obviously, something needed to change.

When I came on as the Senior Technical Product Manager and Lead for our Data and Analytics I was on the hook to make sure these outages would not continue. But that was no easy task. It was out of my wheelhouse to go create events and infrastructure. I knew I’d needed the source code owners help and buy in to get Data Contracts working. This would require asking people, who’s time was already precious and expensive, to add an additional layer of complexity to their work. So how did I approach this conversation and what was my value proposition?

First thing’s first, I came at this problem with a Product Manager mindset. I knew I needed something from the engineers, but I also knew that the current tools they were using for this problem weren’t great. My plan of attack was to first talk to the most data sympathetic SWE we had. He was, first of all, a great engineer, but also very interested in Analytics and what data could do for our business. On top of that, he was a younger SWE and ambitious to try new things.

I had done a lot of research leading up to our first conversation and most of the due diligence with both PubSub and Protocol Buffers. This really came in handy because the engineer I scheduled a meeting with went on to forward it to three other engineers. All of whom came in with an opinion as to why we should/shouldn’t do it the way I was proposing.

I knew that the engineers who worked with on-prem events, specifically, had a major pain point with the current event data pipeline. They were going to be very interested in improving this process. The engineers working on the cloud services, I thought, might have the strongest opinions on my architecture since it’s in their wheelhouse.

My round table for the discussion had the following people:

The Mid Level Engineer who likes data and worked on both on-prem and cloud services.

A Senior Engineer for cloud services

A Senior Engineering Manager for cloud services (pushed back the most)

A Senior Engineer for on-prem services

What is the Value Proposition?

First things first, I needed to understand what my most sympathetic audience would gain by going this route. I proceeded to list out the biggest headaches they had with the current process:

There were only 2 people who were familiar with the codebase to create new events. This created a long turn around time for new people to be onboarded, events to get added, or a new column to be made.

When a new event was created, or a new column added to an existing table, the engineers were responsible for creating the downstream tables in BigQuery, or add the necessary new column. As simple as this would be for a data engineer or the like, software engineers were less used to this and troubleshooting was surprisingly difficult for them.

Anyone could write any event they wanted or add a new column to any current event without needing any sign off on the PR. This caused literal chaos when the person who made the change didn’t correctly update downstream destination tables.

Given the above list, my proposal went as follows:

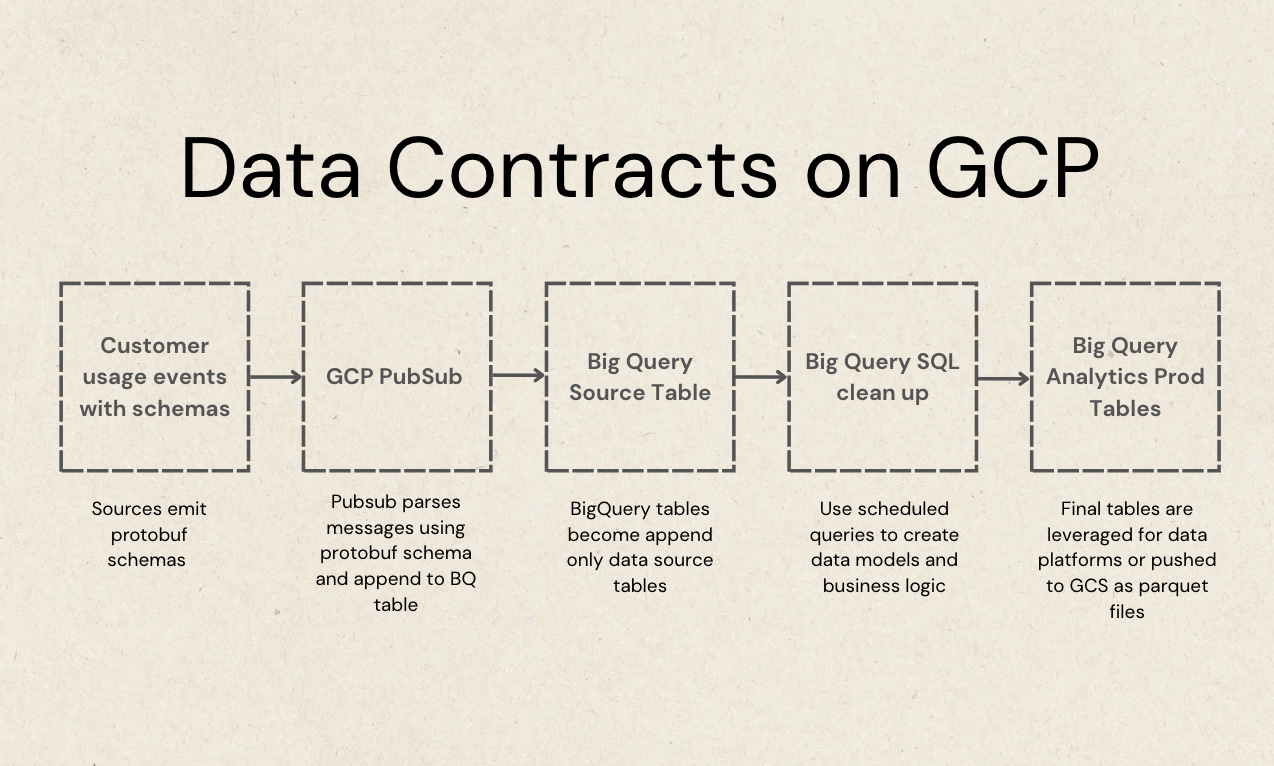

A data source (for the startup we were at, this would be machinery) would emit events for metric specific actions that we wanted to track. The event would be a protocol buffer schema, meeting the protobuf schema standard that GCP PubSub specifically requested (it can vary a little).

I chose protocol buffers over Avro, the other option PubSub offers for this type of pipeline. There were a number of reasons for this, but specifically it came down to how Avro deals with certain nested datatypes vs how protocol buffers do. And while I can’t completely remember the details now, protobufs offered a more concise message schema that aligned with the shape of the current data at the time so I suggested that.

There is a designed event template that everyone has access to. It gives you the schema layout that includes certain required attributes (the data contract metadata) and also the data types that must be used for those attributes. From there, the author is given free reign to look at other parts of the system and bring in attributes they believe would be useful for the particular event that is being emitted.

The event itself is built in code (C# for this implementation) and it must be presented as a PR in the codebase. I proposed that I (as the Tech Lead for Data and Analytics) must be a required reviewer. Before the PR is merged, I need to have approved it. Along with approval, I give the topic name and a sign off that all downstream work is done first.

I handle all downstream set up in GCP PubSub. This includes adding the schema to PubSub, creating the topic correctly for ingestion, setting up a BigQuery Subscription which parses these messages in real time and appends them to a destination table that I also create and monitor.

The destination tables become the source tables for all of our events. Since they are already in BigQuery they are already in an efficient storage structure for analytics (colmnar vs row based).

Scheduled SQL queries in BigQuery were ran every hour to clean data and to build production data models specifically used for analytics. The analytical data models were materialized into tables for quick use in BigQuery, but also exported out as parquet files to a GCS bucket.

A Streamlit app running on GKE ingested the parquet data and acted as our analytics UI.

See this outlined in the image below

You Got the Buy In, Now What?

Doing my best to get ahead of all objections that the engineers might bring up helped me win the round table over. They all accepted my proposal and offered necessary time with them to implement it.

Once you have the buy in, this is where the value proposition you proposed kicks in. I took on the Technical Product Manager role at this point, driving the initiative by roadmapping the milestones, writing all the technical documentation and coordinating the engineer’s time accordingly. The goal is to take on as much technical debt as possible and handle it so that the engineers are simply working in their preferred wheelhouse.

The goal of this Data Contract proposal was not to boil the ocean. We weren’t trying to just create another data swamp by “Capturing Everything”. The events were meant to calculate metrics that would make or break landing a contract with a Fortune 25 company. So not only was this Data Contract initiative important for our own internal work, it was imperative for the future of the business. Fragile pipelines are not scalable or characteristic of a mature software system. Don’t let this work sit idle for long.

How Does the Implementation Work?

From this point you have a decent check list of things you need to make sure are in place.

For all events:

Identify all metrics you want to calculate.

Define each metric with SME’s close to each.

Spec out events that would help calculate each metric with SME’s.

Identify data contract attributes needed for all events and the datatype of those attributes.

This would normally include any relevant id of the event, timestamp or any high level categorical attribute that makes grouping and joining easier (i.e., facility id, order id, customer id or machine id)

Prioritize what events to build first based on metric value and complexity.

Attack low hanging fruit metrics first to get the hang of the event build process.

Create a Dead Letter topic for all events that are not successfully sent to topic to be dumped.

One topic per event. Topics using schemas can only have one schema per topic.

PubSub topic, subscription and schema name semantics figured out.

For example, all topic names fit the same naming convention (i.e. prefix-topic_name-messages, prefix-topic_name-sub, prefix-topic_name-schema).

Understand schema versioning in PubSub and how it works

Have tools in place to convert protocol buffer schema to BigQuery table schema (just use an LLM)

For each unique event:

Get the protocol buffer schema from the PR where the event code is proposed and add to PubSub.

Use the corresponding schema for that topic (done in the UI).

Use the protocol buffer schema to create a BigQuery table.

Create a new PubSub topic with the correct naming convention for the event.

Create a subscription for the topic with correct naming convention.

Use the “Write to BigQuery” delivery type.

Add table information.

Use topic schema for delivery.

Enable Dead Lettering and add dead letter topic created prior.

Create subscription.

Check destination table that data is showing up.

What’s the Next Step?

The above checklist is meant to be your personal take home list so that you have a plan of action on how a Data Contract can be achieved in GCP. If you wanted to take it a step further (which I suggest) then I would even come with a PoC to show the engineers prior to the proposal. They really like to see things in action.

That will require some more technical detail and code. So I am going to follow up this post with a more detailed technical deep dive on how to set this all up yourself (barring permissions). But even if you don’t have necessary permissions via your company yet, you can actually build this all out with your own personal account with no real threat of getting charged anything.

Once that is created we will get a link to that down here and above in the intro. Until then the above should give you a transferable first step for the what and how of Data Contracts!